Asset Publisher

Asset Publisher

Polish forests

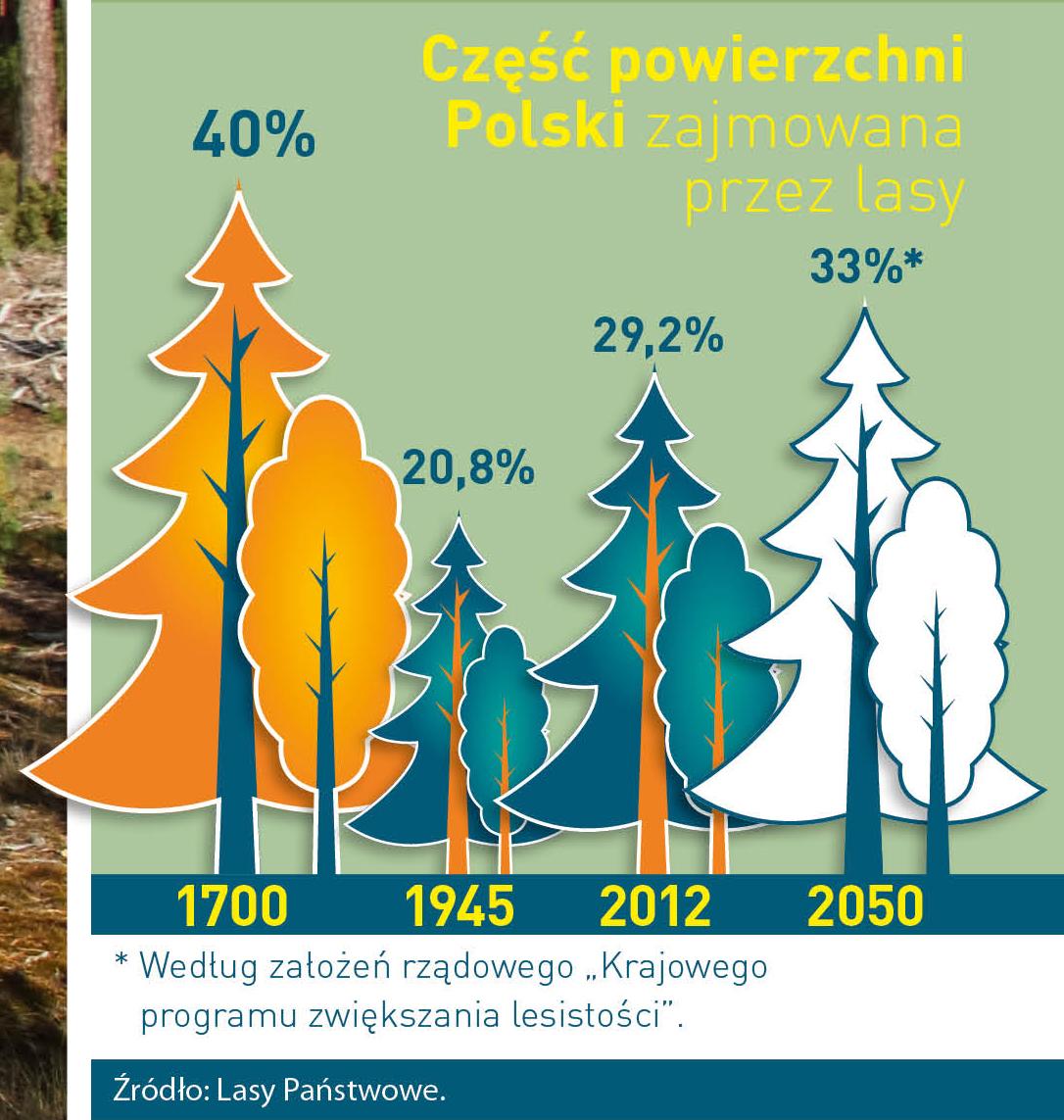

Poland is in the European lead, while concerning the area of all forests. They cover about 29,2 % of the country territory, and grow within the area of 9,1 million hectares. The overwhelming majority of the forests is state owned, of which almost 7,6 million hectares are managed by the State Forests National Forest Holding..

The number of Polish forest is still growing. The forestation rate of the country has increased from 21 % in 1945 to 29,2 % at the moment. Between 1995 and 2008, the forest area increased by 310 thousand ha. The basis for afforestation works is the "National Programme for Increasing the Forest Cover" (KPZL), assuming an increase of the forestation rate up to 30 % by 2020 and up to 33 % by 2050. Polish forests abound in flora, fauna and fungi. 65 % of the total number of animal species live there.

The forests grow in our country on poor soils, mainly because of the development of the agriculture in previous years. It influences the distribution of the types of the forest sites in Poland. Over 55 % of the forest areas is covered with coniferous forests. In other areas, there are forest sites, mainly the mixed ones. Their small part constitute alder and riparian forests – not more than 3 %.

In the years 1945 – 2011 the area of natural deciduous tree stands within the area of the State Forests National Forest Holding increased from 13 to 28,2 %.

Within the lowlands and uplands the most often occurring tee species is pine. It covers 64,3 % of the forest area of the State Forests National Forest Holding and 57,7 % of private and commune forests. In the mountains the predominant species is European spruce ( in the west) and European spruce with beech (in the east). Domination of pine is the result of carrying on sustainable forest management in the past. Once, the monocultures (crops or cultivations of one species) were the answer to the great demand of industry for wood. Such forests appeared to be quite fragile to climatic factors. They also were often the prey of pests' expansion.

In Polish forests, the share of other tree species, especially deciduous trees have been systematically increasing. The foresters have stepped aside from monocultures – that is why, they try to fit specific species of the forest stand to the natural stand, that would be proper for the given area. Thanks to that, in the years 1945 – 2011, the area of the deciduous tree stands within the lands of the State Forests National Forest Holding increased from 13 to 28,2 %. There occur more and more frequently the following tree species: oaks, ashes, maples, sycamore maples, elms, but also birches, beeches, alders, poplars, hornbeams, aspens, tilias and willows.

Our forests are the most often represented by the forest stands aged 40 to 80 years. The average age of the forest equals 60 years. More and more trees are of big size at the age over 80 years. Since the end of the Second World War, the forests' area has increased up to almost 1,85 million hectares.

Raport o stanie lasów w Polsce 2012

Asset Publisher

Asset Publisher

Bliźniacze huby - czyreń dębowy i czyreń śliwowy

Bliźniacze huby - czyreń dębowy i czyreń śliwowy

owocniki czyrenia dębowego

owocniki czyrenia dębowego

Czyreń dębowy

Czyreń dębowy

Czyreń śliwowy

Czyreń śliwowy

Forma rozpostarta czyrenia śliwowego

Forma rozpostarta czyrenia śliwowego

Młody czyreń śliwowy

Młody czyreń śliwowy

Czyreń dębowy

Czyreń dębowy

Czyreń dębowy

Czyreń dębowy

Czyreń dębowy i czyreń śliwowy występują pospolicie w Polsce. Owocniki obu grzybów są wieloletnie i bardzo do siebie podobne.

Czyreń dębowy (Phellinus robustus) występuje w lasach, a także w parkach i ogrodach.

Zasiedla on głównie dęby, a w mniejszym stopniu także buki, głogi i robinie.

Z kolei czyreń śliwowy (Phellinus pomaceus), ze względu na swoje preferencje troficzne, występuje przeważnie w sadach i ogrodach, czasami również w śródmiejskich zadrzewieniach i w lasach. Czyreń ten poraża śliwy, jabłonie, grusze, wiśnie i morele.

Owocniki obu czyreni mają postać przyrośniętych bokiem, na ogół półkolistych lub też kopytowatych, twardych wytworów natury. W przypadku czyrenia śliwowego, bardzo często owocniki przyjmują formę rozpostartą, co u czyrenia ogniowego jest niezbyt często obserwowane. Owocniki rozpostarte przypominają przytwierdzoną do powierzchni, rozlaną plamę gęstej substancji. Wierzch owocników u obu czyreni ma oliwkowo szarą barwę, która z wiekiem ciemnieje i może stać się nawet niemalże czarna. Widoczne są na niej koncentrycznie ułożone bruzdy świadczące o corocznym przyroście nowych warstw owocnika. Brzeg jest zaokrąglony i ma barwę żółto rdzawą, bądź też rdzawo brązową. Hymenofor zbudowany jest z rurek o mikroskopijnych średnicach, których pory u czyrenia dębowego są okrągłe, a u czyrenia śliwowego owalne lub kanciaste. Hymenofor ma rdzawo brązową barwę – podobną do barwy brzegu owocnika, ale z reguły od niego ciemniejszą. Wnętrze owocnika wypełnia drewnowaty, twardy miąższ o rdzawo żółtej barwie. Podobnie jak u innych czyreni, pod wpływem KOH (wodorotlenku potasu), miąższ czernieje.

Czyreń dębowy i czyreń śliwowy, poza podobnym wyglądem, mają jeszcze inne cechy wspólne. Żywot obu grzybów jest bardzo podobny. Zakażenie drzew następuje na skutek wniknięcia zarodników czyreni w struktury drewna. Dogodnymi miejscami do wnikania, a następnie rozwoju zarodników są rany powstałe np. w wyniku obłamania gałęzi lub odarcia kory.

Poza sposobem infekowania drzew, także i skutki rozwoju tych grzybów są takie same. Zarówno czyreń dębowy, jak i czyreń śliwowy, doprowadzają do powstania jednolitej, białej zgnilizny drewna.

Czyreń dębowy jest pasożytem, który na ogół zasiedla żywe i zdrowe drzewa, doprowadzając do rozkładu drewna. Natomiast czyreń śliwowy jest saprotrofem i pasożytem słabości.

Oznacza to, że doprowadza on do zamierania i rozkładu porażonych drzew, jednakże w przeciwieństwie do czyrenia dębowego, jego „ofiarami” w głównej mierze są drzewa osłabione lub obumierające.

Oba te grzyby zasiedlając drzewa doprowadzają do zamieranie drzew i rozkładu drewna. Czyreń dębowy za pomocą swych enzymów uśmierca zarówno młode, jak i te stare dęby – symbol potęgi, mocy i trwałości. Z kolei czyreń śliwowy przyczynia się do zamierania drzew rodzących owoce w naszych sadach, czy też tych rosnących w lasach, wśród pól,

a także drzew wzbogacających zieleń miejską. Takim postępowaniem oba grzyby ukazują jedno ze swoich oblicz – te złe z punktu widzenia człowieka – producenta i konsumenta surowca drzewnego i owoców.

Przedstawione czyrenie, tak samo jak i inne grzyby nadrzewne – rozkładając drewno przyczyniają się do obiegu materii i przepływu energii w środowisku. W ten sposób ujawniają swe drugie oblicze o przyrodniczo ważnym znaczeniu.

fot. Paweł Fabijański

fot. Paweł Fabijański

fot. Paweł Fabijański

fot. Paweł Fabijański

fot. Paweł Fabijański

fot. Paweł Fabijański